A personal testimony on behalf of the City of Noli in Liguria, Italy

by Marcello Ferrada-Noli

In occasion of the 100 birthday of the late Chilean President Salvador Allende, the Region of Liguria and the City of Noli organized a commemorative program. The Vice Mayor of the City of Noli, Prof. Alberto Peluffo, asked me to write a personal testimony on the happenings around Pinochet Coup D’État of September 11th 1973. This is the English version of my text.

Poster by Amnesty International - 1977, of my painting "Esperando al desaparecido. . ." (Amnesty text, Swedish, "How could 2,000 people disappear?") "Although a majority democratically elected Allende as their president, which was killed thereafter, it was only a minority of Chileans which confronted Pinochet with active resistance. Where does courage come from, to do such a thing? Marcello Ferrada-Noli resumes after a long reflection: - It is a question of honour to act according one’s conviction, which is not to be confounded with martyrdom. It is also a question of instinct, an altruistic behaviour such as the person who risks his/her life in saving the life of another person. Perspective must be to see mankind as something bigger than only the ego of our own, and not like the amoeba, that, in Einstein’s words, experiences the drop of water in which she lives of being the universe. When there is no other available alternative, the one who fights has nothing to lose but his own oppressed existence” / Dagens Nyheter (DN) interview with the author, “Professor has sailed in dangerous waters”, DN 17/7 2008.

Poster by Amnesty International - 1977, of my painting "Esperando al desaparecido. . ." (Amnesty text, Swedish, "How could 2,000 people disappear?") "Although a majority democratically elected Allende as their president, which was killed thereafter, it was only a minority of Chileans which confronted Pinochet with active resistance. Where does courage come from, to do such a thing? Marcello Ferrada-Noli resumes after a long reflection: - It is a question of honour to act according one’s conviction, which is not to be confounded with martyrdom. It is also a question of instinct, an altruistic behaviour such as the person who risks his/her life in saving the life of another person. Perspective must be to see mankind as something bigger than only the ego of our own, and not like the amoeba, that, in Einstein’s words, experiences the drop of water in which she lives of being the universe. When there is no other available alternative, the one who fights has nothing to lose but his own oppressed existence” / Dagens Nyheter (DN) interview with the author, “Professor has sailed in dangerous waters”, DN 17/7 2008. It is estimated that 30.000 people were killed in the aftermath of the U.S.-sponsored military coup in Chile of September 11th, 1973. Combatants of the leftist organization MIR and from other leftist parties offered active resistance to Pinochet’s army on the 11th of September. However, the resistance to the military takeover was in general sporadic, with low firepower, and did not prevail. In other words it did not occur in the scale expected, or planned. We in MIR were at that time on high alert (see below Plan Militar de Emergencia), psychologically prepared “for the moment to come” and for the relevant activities. Moreover, we new (and even provided Allende with intelligence on the coup-preparation) that the putsch was imminent.

But the open direct resistance was crushed very soon, and also due to the brutality of Pinochet forces the core-militants did not succeed to encourage the mobilization of the vast majority of Allende supporters in order to take up the fight together.

Yet another aspect it was that Allende himself warned (on the very 11 of September) the supporters that have elected him, of not taking unnecessary sacrifices. I was in Concepción at the moment of the coup and at that time with assignment in the Organization detail of the Regional Committee, meaning that my “structure” was of a “central” kind. Three of the five members of the detail were captured. I spent times at different detention centres such as the Stadium, the Navy’s camp of prisoners at Quiriquina Island, the “marines” detention quarters at the Navy base in Talcahuano, and finally back to the Stadium in Concepción.

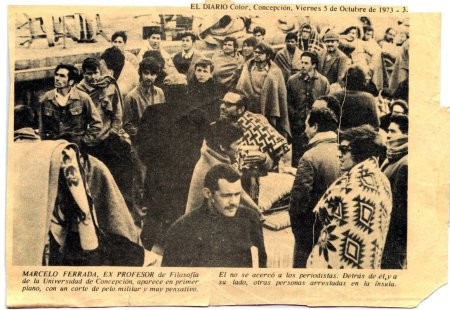

Many died in these places either under torture or executed by firing squad. For instance, in the photo here below taken at the prisoner camp of Quiriquina Island and published in the front page of the mayor Chilean newspaper ”Tercera de La Hora” (6 of October 1973), is mentioned the Intendente of Concepción Fernando Alvarez (head for the Regional government at the moment of the coup), at the centre of the picture. In fact, he died under torture at the camp in Quiriquina Island some days after that picture was taken. I am also depicted in the same photo, upper right (indicated by the red arrow). The photo was taken during a visit of the Red Cross International at the camp. This fact did enable, or forced, the public "recognition" that I was held prisoner – instead of risking the standard status of “disappeared" person.

Translation of the text (first part) in the caption of the newspaper's image:

"The extremists, and the local authorities of Concepción of the past marxist [sic] regime, have been imprisoned at Quiriquina Island. The first ones [the 'extremists'] are there because they have attacked the military forces with firearms".

Three factors have contributed to obscure the real magnitude of the resistance on the 11th of September and the days ensued. One is the reluctance of the putsch leaders of acknowledging the true magnitude of their casualties. Doing this would have shown that the resistance was effective and thus motivating its continuation. A second factor is that the far most of the operations were of clandestine character. Also, due to the fact that all the press, all TV channels and all radio stations were seized the 11th and remained under the direct control of the military (not only by decree, but physically under control) it was not possible either to communicate eventual results of the actions.

A third factor is the “factor seguridad” of the militants and units involved. As cadres become arrested in increasing numbers, the units or combatants acting with own initiative tightened security to keep knowledge of the actions to the absolute minimum, or even unknown. For instance, not even the closest members of our families, spouses, etc. would know or suspect what had really happened. This ignorance would save them too. And that silence continued for the years to come, no matter that many lived then in exile. However, an unequivocal recognition from the part of the military authorities on that the active resistance in Concepción took place in form of armed attacks is given in the text of the photo of La Tercera (6/10 1973) above.

I was then 30 years old and a professor at the University of Concepción. Having worked previously as invited professor in Mexico with books published there etc, I was released from captivity partly after direct demands from Mexican academic scholars and authorities (pressures and solidarity came also from colleagues in Italy and Germany), and partly after demands from my family which had strong tradition among the military. I was not set free in Chile but expelled from the country directly to Mexico from the prison, escorted to the airport by the military.

I had to sign in the airport a document committing me of not to speak about the atrocities in Quiriquina Island etc. However, I changed route in Lima (the first stopover in my way to Mexico), from where on instructions of my organization I went directly to Rome, Italy, in order to participate in the Russell Tribunal which had started in Rome on the crimes of Pinochet’s junta. I was main witness at the Russell Tribunal and thereafter member of the scientific committee of the Russell Tribunal together with writer Gabriel García Márquez, Linda Bimbi, and Senator Lelio Basso. Thereafter I was sent to Sweden where my last assignment from MIR’s Comité Exterior was to organize intelligence work for the counterattack to Pinochet liquidation squads in Northern Europe, activity which I lead until 1977. I resigned all my activities in MIR in June 1977, during the MIR Conference in Stockholm.

Part I

September 11th, 1973

It was a very shiny seven o’clock, that morning of September 11th 1973 in Concepción, the largest city of southern Chile. I was then staying at the family country house some 20 kilometres north of the University campus, where not so long ago I had been appointed professor of psychosocial methods. I have come back from México some months before. Going out towards the garage, the meeting of a sunny day made me decide at the last second to ride instead my motorcycle to the job. As it did show, it was a spur-of-the moment decision that most certainly save me from being captured, tortured, and killed that very same day.

Nearly exact three years ago had Allende became the first democratically elected president in the western world. I was then 27 years old and living at that time in London, and I decided to come back immediately to Chile. During those first years, the structural changes made by Allende’s government in favour of the less privileged sectors of society, and that to certain extent were to be financed by the nationalization of the Chilean cooper mining industry – then exploited by private USA corporations – brought about many powerful enemies to him and his government from both in and outside Chile.

The biggest and most important parties of the centre-left coalition that supported Allende’s government were yet in good faith convinced that the vast popular support to Allende together with the democratic credentials of his government would indeed avert any serious political attempt against the “gobierno popular”. On the other hand, a tiny minority voice within the left ranks, mainly represented by MIR – the revolutionary left movement – was pretty convinced that Allende government was not safe, and that a coup d’état would be imminent. With thesis as point of departure, MIR had instead prompted Allende to secure his support among the masses by deepening the socialist measures in their favour. At the same time, MIR started to do some preparations to resist militarily if necessary, and seriously thought that such resistant could be prosperous when the time would arrive.

The facts probed, fatally, that both theses were equivocate. Pinochet and his generals were not only well militarily prepared but their mission well assisted and even organized with powerful help from abroad, from the land of the foreign owners of the Chilean mines.

In short, using drastic and brutal over violence, Pinochet generals and their allies seized militarily the power that has been denied to them politically by the course of the democratic polls. With all, the most effective tactic of Pinochet operation was the consequent concealing of his purposes to his chief, President Allende, to whom he had swear loyalty until the last moment. Not even MIR, in spite of all the intelligence was able to gather about the coup preparations, was able to predict the very date of the putsch.

Consequently, that morning of the 11th of September, while I was riding my motorbike to Concepción, entering Collao Avenue, I was not aware that Pinochet troops were since earlier setting up checkpoints and stopping every single car or bus going downtown. The military were in search of combat weapons and looking for cars transporting persons whose names were in their arrest-lists. They did let pass through only single walkers, and when it was clear at first sight they could not be wearing combat weapons.

The military and the police forces collaborating with them in the preparation of the military take-over have their lists, exactly like Gestapo. In these lists were all the authorities appointed by the government, all the trade unions leaders (not only of national or regional organizations, but of every single union leader at the working sites) and the leaders of the left political parties and organizations, the academic and intellectuals with left sympathies, the leaders of student organizations, etc.

I dare to say that my odds were not the best. I was at that time member of the leadership of the association of university teachers and workers, which was my public political assignment. Besides, as a young university professor graduated in philosophy and recently having published a book [1] which – although its mainly philosophic content – I had expressly dedicated it to an Indian leader of the agriculture workers (Moises Huentelaf, who fallen death 1972 by the bullets of the powerful landowners of Southern Chile), I was indeed considered by the military among the so-called “left intellectuals”. Not to mention I had published articles in the independent leftist magazine “Punto Final”. And “worst” of all, I have been one of the founders of MIR back in October 1965 and also co author, together with long-time friend Miguel Enríquez (MIR’s leader) and his brother Marco Antonio, of the first “Tesis politico-militar” of MIR approved in the constituent congress [2]. Although no more than eighty people from all along Chile was present at the constituent congress of 1965, at the time of the coup, 1973, MIR had grown to thousands of supporters, and many of them core-militants. For the first time, I will also acknowledge here that my clandestine political role as MIR militant was member of the Organization Committee of MIR for the Region Concepción.

As I saw increasing checking points I left the motorcycle and continued more discretely per foot towards Concepción. As I was already in the way towards the University I decided to get into the house of Avenue Roosevelt 1674, the residence of Dr. Edgardo Enríquez Frödden (see here) which was then living in Santiago in his condition of Education Minister in Allende’s government. I knew that his son Marco Antonio, one of my closest friends (brother if Miguel Enríquez) was living there. Marco Antonio Enríquez was a scholar from Sorbonne university in Paris which also had come back to Chile. There we were updated of the happenings via the radio. Pinochet coup had started in the Navy base in Valparaiso and coordinated with Army troops in Santiago. They were now moving around the President Palace “La Moneda” in downtown Santiago.

From the Enríquez’s place I called the “central” but it was not operative that early. In the meantime we saw the army trucks, full lasted with soldiers, going in direction to the university campus. At aproximately10.30 I made finally contact and I was given a “punto” (meeting point) in Concepción downtown, specifically at the exit Maipú Street of Galería Rialto (if I remember the name well), to receive details of the orders.

At that times MIR had prepared, nation-wide among its core organization, a military-political organization based in the “GPM-structures” (“grupos político-militares”). This means that every single militant, regardless his/her public political commitment, was member of a concrete GPM. These GPMs, also called “structures”, were in turn organised in clandestine military-political cells (“las bases”). In my particular case, being at that time working clandestine at the Organization detail of the Regional Committee, my GPM was the one called “the centralized structure” and my operative cell was the detail itself, integrated at that time by five members (of whom three have survived, all of us living in different countries in Europe).

The main contingency strategy of MIR for the eventuality of a putsch was contained in the nation-wide “Plan Militar De Emergencia” (PME), according to which every single GPM, and its turn every concrete cell, had a previously assigned geographic area to act upon politically and militarily during the planned resistance. Up to my knowledge, every single MIR militant have had some military training. Apart of the cells mentioned above, existed at MIR also a few so-called “grupos de fuerza”, integrated with militants with a certain degree of specialization for this kind of resistance task. For instance, during the months prior the coup, the training coaches of MIR ranks used to belong to those structures. Some of them, also as militants of MIR, had previously served as bodyguards of President Allende. Nearly all of them are now dead.

The organization cell which I belonged to – as I said before pertained to the central structure of MIR in Concepción - had been assigned combat stations precisely in the centre part of Concepción City. This posed a terrible problem for me, personally, since my parents lived in the building of Colo-Colo Street and Avenue San Martín, two blocks from the Concepción “Plaza de Armas” and were the government offices were located. This means also that near my parent’s residence was situated (circa two hundred meters towards the opposite direction) the head quarters of the Military Division of the garrison Concepción are (at O’Higgins Street and Castellón Street)! Also my son and his mother have been sheltered at my parents’ residence; this after my father went to the country side and brought them to “safe”. In fact, Pinochet forces have had – during my absence – a siege to the property at the country side on the afternoon of September 11th.

The resistance in Concepción, and in Chile as a whole, was not done at the scale that MIR had expected, although numerous combats took place in several sites all over the country. In this fight participated also militants from other political parties of the left. In Concepción, sporadic skirmishes were reported regarding the nights of the 11th and 12th of September, both in the centre of the city and in some point of its periphery. And this was supposed to be according to the plan.

After 35 years it is not possible to be exact without the documents in hand, but, as I recall in gross terms, the PME had among other items in its strategy these four moments to be implemented: a) MIR cells assigned for combat in down town were not to seize positions or barricade but to develop hit and run operations in multiple targets with the principal focus of distracting Pinochet forces from the combats in the “cordones industrials”. b) These so called industrial cordons were the regions in the outer perimeter or outskirts of the city where factories were allocated, and also many “poblaciones” – the living areas of that time for the working class and the poor. Here it was previously organized, and predicted, severe resistance to the military forces. c) The cool mining workers from Lota and Coronel, cities near Concepción, were “expected” to cross Bio-Bio Bridge in a mass march (a political demonstration, not necessarily with arms) towards Concepción and thus reaching first the city’s periphery where the workers would unite with the people in the cordones. d) The battle would continue pushing the military towards the centre parts of the city and were they had their head quarters and also the three regiments were located.

The only aspect I can personally testify is the one related to the night “enfrentamientos” (perhaps more properly referred as sporadic “fire exchange”) from some roofs of buildings in Concepción down town the 11th and 12th of September. They did exist. And I also remember vividly some sounds of explosions and the sound at intervals of automatic fire, heard long away from downtown, during those two days. As a matter of fact, in a visit I made to Concepción in 1984 (my first visit to Chile after my exile in Europe) the impact of bullets were still visible on the walls and stairway of the building were my parents lived, in Colo-Colo St. and San Martín Av., and in the big neighbouring wall of the Hotel Alonso de Ercilla. Most certain are that those marks have survived in one or another fashion under the make up. They were too big and too many to conceal by cosmetics.

On the other developments, I never knew for real what real happened at the “cordones industrials” of Concepción. We heard the automatic fire and some heavy explosions-sounds that came from the city’s outskirts. Mostly the very same day of September 11th. I met some comrades both at the stadium and at Quiriquina Island who were assigned to that front. But one fundamental rule (for one’s survival and the rest’s) is that you never, ever, ask your comrades in captivity on “how did it go” on such matters. On the other hand, I certainly know what happened with the projected march of the mining workers.

According to the information I have, the head of MIR’s Regional Committee in Concepción, which was supposed to have the ultimate responsibility for the political side of the PME would have ordered MIR militants in Lota and Coronel – in spite of the orders contained in the PME - to halt the march towards Concepción. He visited me at my residence in Stockholm in 1980 and after his account of facts I am prone to believe the version I had heard from before that he tried to halt the march in order to avert the almost certain massacre that march would eventually end in. Indirectly, this is a clear acknowledgement for us that the resistance against the deployment of military Pinochet forces in Concepción did not achieve the goals of the PME.

Personally, I was first publicly declared dead at the combats of Concepción, which in the beginning occasioned much problem during my first time in military captivity, as I explain down below (in order to survive torture, it existed the praxis to attribute to the perished combatants the responsibility facts and whereabouts searched by the interrogators). In fact, I continued moving myself in clandestine forms in Concepción, and in regular contact with our operative-liaisons (females all of them. Known as “las compañeras de la central”), until the order of cease operations and “submerge” was given to me by her and as it was contained in a communication from MIR leadership in Santiago to all the GPMs which had survived in Chile.

We could sum up that in that period the armed resistance to Pinochet’s forces was defeated, but not perished. The year after, being in Rome, I painted the piece “Vinta ma non sconfitta” which also was the motive of the poster for an art exhibition organized by the publishing house Feltrinelli, here below:

As MIR cadres were abated and our logistics became more and more precarious I have to mover more and more often between safe houses. MIR transports were in a moment extremely scarce or too risky to use, and I had finally to rely in my family for such transports. “Safe houses” were at the end just places of people around your private life, acquaintances without political bounds, or places dangerous per se. This was the case of the last safe house I could count with, in the northern sector of Concepción, and actually belonging to the maid employed at my parents’ residence. What I did not know it was she had a relationship with a sergeant of the Regiment Chacabuco. I call my father immediately to come and pick me up but the car was detained “for driving after the curfew”. I never knew if it was a set up. My family is indeed right-wing and many were, and in later generations still are, officers in the armed forces or in the Navy. On the other hand this fact contributed that I am still alive.

I was taken first to the Stadium in Concepción. The morning after I was lined with two other prisoners waiting execution – right under the goal frame – by firing squad. One of the fellow prisoners was the former executive director of the state-owned SOCOAGRO in Chillán, and the other was a 16 years old worker from a “cantera” (sort of stone mine) caught with explosives apparently taken from the mine. I was recognized by a petty officer years before serving under my father’s command. I was saved, and it was not going to be the last time. For more details, read the text by Anna-Leena Jarva - based on my testimony and other documents - in Ferrada-Noli VS. Pinochet, (Go down to Part II, The Aftermath).

Part II

Prisoner in Quiriquina Island

Torture "Pau de arare". Painting by Arte de Noli, exhibited at Kulturhuset, Stockhom 1977

Torture "Pau de arare". Painting by Arte de Noli, exhibited at Kulturhuset, Stockhom 1977 The author, prisoner at Quiriquina Island

At the time of General Augusto Pinochet’s Coup D’état I was mobilized in the organization-unit belonging to the GPM (Grupo político-militar) of the Comité Regional Concepción of the MIR. The actions were already set for each GPM and its units in the Plan Militar de Emergencia (PME) which prevailed in MIR in anticipation of the Coup D’état. This plan was not in the main followed by MIR in Concepción. Partly due to the Nr 2 ordinance (comunicado nr 2) distributed by the Comite Regional the 12 of September in which we were asked to “wait and see”. I received this communicate in hand through personal courier, in a rendezvous sat in Maipú and Aníbal Pinto street, close to Galería Rialto, where the Communication and Telephone Central of MIR in Concepción had its clandestine quarters in the second floor (“La Central”). This was also a centralized unit ad hoc the Regional Secretariat of MIR. The unit’s task was also the decoding of the encrypted messages coming from MIR command in Santiago (“La Comisión Política”, led av Miguel Enríquez). The communiqué was given to me by one ot the three militant-girls ascribed to La Central ( ”H”, I have her name), and she said were instructions of the Secretario Regional of MIR in Concepción.

Sharing my first safe house – already from early morning of September 11 – with Marco Antonio Enríquez (elder brother of the leader of MIR) in Avda Roosevelt near the University campus, we questioned the authenticity of such comunicado nr 2 apparently contradicting what we knew of Miguel’s activities in Santiago. Thus, in trying to adjust to the Plan, I changed again to a safe house located ad hoc a Pharmacy in Barros Arana Street – in the vicinity of a building of the Carabineers – to monitor troop movements. We choosed safe-houses only located in central Concepción or around military compounds, in order to deal with the curfew-situation, which otherwise limited our night operations (situation – regretfully - not contemplated in the PME). The first house, rather big, was owned by a family of Allendes’s sympathizers which also run there a Pharmacy. We initiated nocturnal actions in central Concepción the first night after September 11. However, since in the house were also hidden various non-combatants Allende sympathizers, ultimately we were asked by its owners to leave the premises, in fear of a searching if we would be followed or captured.

If I remember well, these actions were reported by the newspaper “El Sur” the 13 or 14 September, with a picture of fire-giving from the roofs in central Concepción.

I was later captured while transported under curfew by my father (a former officer) obliged to leave suddenly my fourth safe house and with no contacts left in the organization. The head of the Comisión de organización (my unit) was captured in Las Higueras and taken to Quiriquina Island were I later met him heavily tortured. He never talked and saved thus several lives (he is now a doctor exiled in Holland). La Central at Galleria Rialto had been closed down by MIR’s initiative.

My father did not know anything beyond that I was “on the run” and in need of help for transport that night. Having my father right-wing political sympathies, I did not carry anything that could compromise. The vehicle was intercepted by an Army patrol in Las Heras street. At the spot identified only as a Professor of the University of Concepción (closed down by the military the very day of the coup) and not as militant of MIR, I was taken to the Football Stadium in Concepción. However – as courtesy to the family this transport under the custody of Artillery officers under my brother’s command (at the time a captain in the Artillery Regiment, and whom my father contacted immediately). It was not the last time he would save my life.

The Stadium in Concepción was a first detention portal of unprocessed detainees. DINA did not exist at that time yet, and the Intelligence and repression activities at the Stadium coexisted with the ordinary logistic and security “taking care” of the prisoners. The Intelligence activities carried our in the beginning by an hybrid ad hoc pluton integrated by officers and petty-officers of the Army, Carabineers, Political Civil Police (Servicio de Investigaciones, and the repressive part performed by brutal ordinary staff and officers of the “Gendarmería” (ordinary prison or jail-guards formations). The logistic and security tasks were in charge of a company from the Army.

Here at the Stadium of Concepción the detainees were sorted according to political hierarchy and participation character (political or insurgents). Most of the categorised as political cadres, militants or profiles and leaders of the Unidad Popular (Allende’s political coalition) and MIR, were taken from the Stadium in Concepción, airborne, to a camp in Northern Chacabuco.

On the other hand, political leaders with suspected responsibility in former “subversive” preparedness (the so-called ”Plan Z”, an euphemistic denomination found by the Military Junta to refer potential subversive capability), or cadres suspected of participation in resistance activities, were either shot or taken for further interrogation to Fuerte Borgoño (Marines) and eventually to the prisoners camp in Quriquina Island. In these two compounds were also executed several prisoners. Eventually, later in 1974, some few prisoners in Quiriquina Island which after re-evaluation met the “Chacabuco” criteria (se above), were again gathered at the Stadium in Concepción and together with other prisoners (59 in total) sent in an Air Force Hercules to the Chacabuco Camp.

For my part I was identified by Intelligence officers at the Stadium as militant of MIR, and suspected of resistance participation. First I was in the line to be shot – at the orders of Teniente de Gendarmería Vallejos - together with two other prisoners, the former Director of Socoagro in Chillán and a young adolescent detained when carrying dynamite he had taken from the Cantera he worked at. We were saved from under the Stadium’s Southern arc at last-minute by the intervention of Capitan Sánchez, the commander of the Military company at the Stadium (more of this dramatic episode in the biographic report “The red, the black, and the white“ ).

From there I was taken together with a number of other detainees to the Navy Base in Talcahuano, where a concentration of detainees from elsewhere in the military region took place. Here were selected after further investigation those detainees who would fall in the military jargon under the category ”prisoners”, meaning that they would be held in captivity at the infamous Quiriquina Island Camp. But some perished under torture or were assassinated.

Quiriquina Island

The author, prisoner in Quiriquina Island. See picture at left

I arrived at Quiriquina Camp with eleven other prisoners. Two of them had come as detainees from the cool-mine city of Lota and were shot at the Quiriquina Camp short after we had arrived. One was of the name Carrillo, a trade union leader in the mining zone and heroes of the resistance against Pinochet.

When I entered the main gate in the “Gymnasium” – where at the time all the about 800 prisoners were kept together in one local – my comrades in MIR were surprised, to say the least. The reason was that I have been reported dead in the Concepción actions. One of the prisoners which received me, a young student of name Quiero, even said to me that in Coronel (a mining city in the Region) they have set a hit-unit called my name, as honours to the dead in action!

Also Miguel Enríquez got the report of these actions and my presumptive death. This was told to me in Malmö in 1976, by the compañera of Alvaro Rodas (an old-timer from the VRM period, and if I remember well, member of the first Central Committee of MIR). According to what she told me in occasion of a MIR-meeting (cells of MIR for the ”trabajo de apoyo exterior”) we had in their apartment in Malmö, she heard herself from Miguel that, literally ”calló Ferradita” (Miguel used to call me Ferradita) and that he was affected by it.

The above situation – that I was believed by many comrades killed by the military in Concepción - had important, and even determinant, positive consequences for my survival at the Camp and at the interrogations under torture.

For those not acquainted with clandestine operations under severe violent military repression, it will be perhaps difficult to understand what follows. The fact is that before I came to the Quiriquina Camp, various of my comrades - interrogated under torture – blamed me for the personal responsibility or executor of the particular operations or activity these comrades were suspected to have had in MIR. The “blame the dead” was a necessary tactic of survival that spontaneously grew in such torture centres.

The above in turn served me as a miraculous survival tool under torture. For when the agents asked me about all kind of items including the items which were truly my responsibility, I invariable responded that “naturally” nothing of that was – altogether - true, for the source of those reports on my doings was most certain the practice of “blame the death”, and that I had left my active contacts with MIR (I could not deny that I was a founder of MIR, but “that was historic”) for long time ago when I became Professor at the University of Concepción. All wich the interrogators finally accepted after several weeks.

In conjunction with above, it is important to understand the nature of these interrogation processes at the Quiriquina Island.

a) The interrogations were NOT carried out in the first place by the personal in charge of the prisoners or the Navy personnel at the Island. Instead the interrogators were Intelligence personal from the Carabiners, the Army, and the Navy, which travelled episodical and constantly to the Island to exercise their sinister task. Also, they belonged at that time to their respective Intelligence departments. Situation changed after that time with the creation of DINA, Pinochet’s Dirección Nacional de Inteligencia.

b) These individuals rotated constantly. At least under my time at the Quiriquina Island (one), at the Detention centre at the Naval Base in Talcahuano (twice), and at the Regional Football Stadium in Concepción (twice). At Quiriquina Island the arriving interrogators some times were only Carabineers, or only Army, and some times a mixture from all services.

c) 1973-1974 it was a time of no computerised information, no data files reachable with a click. Instead the information was gathered in notes taken by the interrogators themselves under a situation in which they were at the very same time the torture-agents themselves.

What I mean – in the context of my experiences at the Quiriquina - is that this constant rotation meant that many of the items asked to me in those interrogations were based only in note-reports taken from other agents in different occasions and before I got in the Island. All which made less difficult for me to play the convincing survival plot described before, added that the agents interrogating me were not those with the relevant hard data.

Four decades. Graphic by Armando Popa, 2009. Basedon Portrait of political prisoner Armando Popa (Ferrada-Noli 1973)

But that was of course not the ultimate reason of my survival, of why my true role in MIR at the time of the Coup and in the actions afterwards was never known by my captors at the Quiriquina Island. The reason, as I see it, is because those who actually knew of my activities, such as the head of the Organization Detail of the GPM Regional Committee of MIR in Concepción I truly belonged to, and not only the front political unit at the University of Concepción. This friend is Renato Valdés, a doctor living now in Holland. He never revealed anything, never talked at the interrogations even under heavy and prolonged torture.

It was everything so dramatic. Every time one of our comrades was called by complete name in the loudspeakers and asked to report himself at the gate of the huge collective cell (the gymnasium) to be taken by the marine-guards to the interrogation/torture sites. Another time, any time, it would the turn again of any of us who were left for the time being in the uncertain waiting list.

It was on those circumstances which I remember most vividly Renato Valdés, which is a situation I am sure characterizes the situation of any of the prisoners of MIR at the Quiriquina Island. Coming back from interrogation after hours of us waiting anxious for his eventual return. And the dramatic mixture of feelings while two or three comrades sat around him on the floor of the gymnasium:

Disappointment, because in the best of cases he could have set free. Relief, by the fact he was still by us, and otherwise he could have resulted much worst, including the risk of perishing under torture. Sadness, because of the horrible shape – physical and psychological – that those interrogations inflicted in all of us. And finally, the satisfaction and proud that he survived the interrogation without saying anything that could compromise us.

See also

I

While we were at Quiriquina Island, I made in the hide this portrait of Armando Popa, a fellow prisoner. The portrait is from December 1974. Popa and his younger brother - also in captivity at the Island - come afterwards to Sweden to work as doctors.